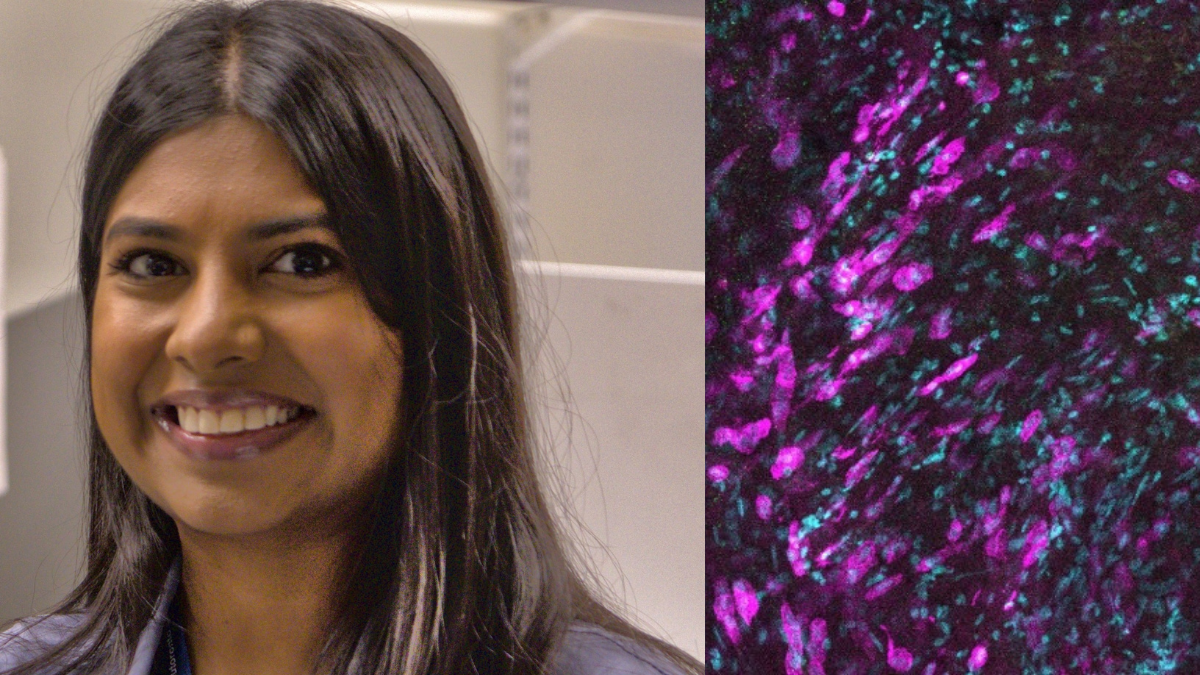

Sumiha Karunagaran (left) is investigating how immune cells in the pleural cavity (right- shown in pink) respond to bacterial infections of the lungs

April 17, 2025

By Sunitha Chari

Lung transplant recipients are on lifelong immunosuppressant drugs to reduce their risk of organ rejection. This makes them incredibly susceptible to bacterial infections, with scientists and clinicians continually investigating ways to help the body both accept the transplanted organ and minimize the risk of infections.

Pleural immune cells that reside in the pleural cavity could hold some answers. While their existence has been known to the scientific community for a while, limited access to human lung tissue samples has stymied detailed research into them. Consequently, little is known about these immune cells and their association with lung infections.

“Pleura is the membrane that lines the chest wall and wraps around the outside of the lungs,” says Sumiha Karunagaran, a fourth year PhD student in the department of laboratory medicine and pathobiology at the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine. “And between these two layers of the pleura, lies a space known as the pleural cavity.”

Karunagaran, who is one of 25 recipients of the Emerging and Pandemic Infections Consortium Doctoral Awards, aims to address gaps in the understanding of pleural immune cells.

Working in the Toronto Lung Transplant Program at the University Health Network (UHN) — one of the largest lung transplant programs in the world — her research combines imaging of mouse and human lung tissue samples with single cell analysis of pleural immune cells to investigate their role in inflammatory responses.

“I chose transplant immunology because it is a fascinating biological problem, one in which we are actively trying to counter the body’s natural immune response to a foreign object,” says Karunagaran, who is supervised by Stephen Juvet, a respirologist at UHN and assistant professor of medicine and laboratory medicine and pathobiology at Temerty Medicine.

One aspect of her research involves investigating how bacterial infections affect pleural immune cell behaviour and functions. To this end, Karunagaran has developed a mouse model to study the inflammatory responses mounted by pleural immune cells to an infection signal such as lipopolysaccharide, a cell surface component found on infectious bacteria.

Her research findings suggest that pleural immune cells exist as free-floating cells in the pleural space and upon exposure to an inflammatory stimulus, they start sticking to the surface of the lung in what she calls “immune clusters”.

Immune clusters lead to the formation of scar tissues and in chronic lung inflammation that persists in response to lingering infections, the buildup of excess scar tissue results in pulmonary fibrosis. Fibrosis is a condition where lungs lose their elasticity, affecting the individual’s ability to breathe properly and severely impairing lung function.

Her current research efforts aim to characterize the free-floating immune cells and the clustered cells using a technique called CITE-seq. “Using CITE-seq, we can identify the different populations of pleural immune cells based off their surface protein composition and begin to understand their potential functions by their RNA expression profiles,” she explains.

Karunagaran notes that the data from the CITE-seq experiments will shed light on the different types of immune cells present within the pleural space to a level of granularity not known before and will form the basis of experiments to investigate the mechanisms by which these immune cells go from free floating to the cells that form immune clusters.

Her research offers a first look at the involvement of pleural immune cells in bacterial infections and could inform the development of new therapeutic strategies.

“We believe that any inflammation in the lung initiates pleural immune cell responses; therefore, targeting the pleural space can be an effective method to not only improve transplant outcomes but also to treat other chronic or severe bacterial infections,” says Karunagaran.