In honour of Black History Month, we are pleased to feature a series of stories celebrating the contributions Black individuals have made to our understanding of infectious diseases and how to prevent and treat them. Each story is written by a member of EPIC’s Trainee Advisory Committee. Check out the other stories in our series here, here and here.

February 29, 2024

By Suji Udayakumar

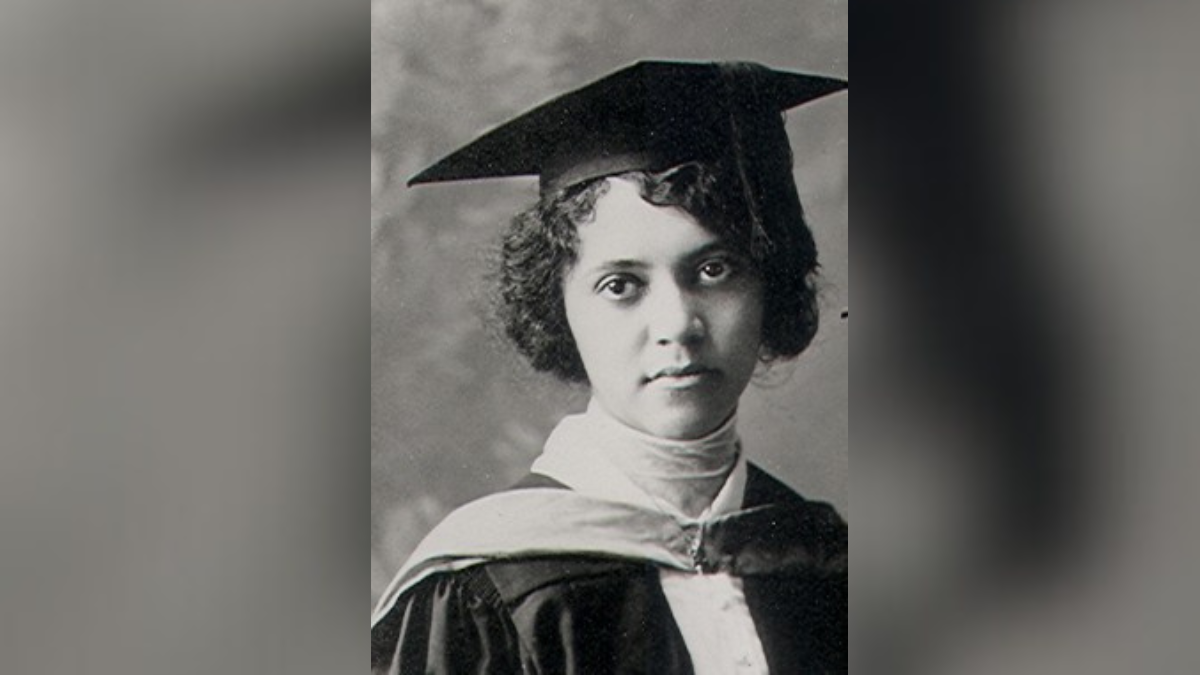

Alice Ball was an African American chemist who revolutionized the treatment of leprosy through modification of chaulmoogra tree oil’s chemical properties. However, she did not receive credit for her contribution for over half a century.

Alice Augusta Ball was born on July 24, 1892, in Seattle, Washington. Her mother, Laura, was a photographer, and her father, James P. Ball, Jr., a lawyer. She had two older brothers, and a younger sister.

Ball excelled in science throughout her education. She was one of few in her high school graduating class of 1910 to concentrate in its scientific program. She earned two Bachelor of Science degrees in pharmaceutical chemistry and pharmacy from the University of Washington.

During her undergraduate studies, she collaborated with University of Washington chemistry professor William Dehn to publish findings regarding benzoylation in a prestigious journal.

Alice Ball was the first African American, and the first woman, to graduate with a master’s degree in chemistry from the College of Hawaii (now known as the University of Hawaii). She went on to become the institution’s first woman chemistry instructor. In her master’s studies, she wrote a 44-page analysis on the chemical properties of the kava plant, which is native to the Pacific and known for its relaxing qualities. This was read by Harry Hollman in 1915, who was a physician and bacteriologist at Hawaii’s Leprosy Investigation Station. He contacted Ball to ask for her assistance in investigating another plant’s chemical properties: the chaulmoogra tree, whose foul-tasting oil was a folk remedy for leprosy.

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, is an infection caused by the bacterium, Mycobacterium leprae. It could cause paralysis, disfigurement, and nerve damage. The condition was associated with a lot of stigma and those with the infection were forced into quarantine.

Through a series of difficult and elegant steps, Ball was able to identify the chemical secret to the oil’s effectiveness. She identified its main components and isolated its active ingredient, constituted fatty acids, which she was able to convert into a water-soluble form that could be injected safely.

When Hollmann tested her treatment on his patients, he saw that it could kill the bacteria that causes leprosy and improve symptoms. He acknowledged her innovation, which transformed chaulmoogra into an easy-to-administer leprosy medicine and coined the term “the Ball Method” in his 1922 paper published in the journal Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology.

“After a great deal of experimental work,” Hollmann wrote, “Miss Ball solved the problem for me.”

Ball’s method helped reduce lesions and alleviate pain for thousands of individuals and was able to free many from quarantine in isolation facilities. Her method was distributed worldwide and used for over 30 years until antibiotics were developed.

Despite her important contributions to leprosy treatment, only few knew that Alice Ball was the developer of the Ball method. She died in 1916 of accidental chlorine gas inhalation before she could publish her findings. Her breakthrough was claimed by Arthur Dean, who was then president of the College of Hawaii, and Richard Wrenshall, a chemistry professor. They published her findings in two journals and did not mention her name or her contributions. Indeed, Dean capitalized on Ball’s research by naming it the Dean method after himself.

It took over fifty years for Ball’s contributions to be uncovered and for her to be recognized as the true developer of the chaulmoogra treatment.

In 2000, the University of Hawaii-Mānoa placed a bronze plaque in front of a chaulmoogra tree on campus to honor Ball’s life and her important discovery. Former Lieutenant Governor of Hawaii, Mazie Hirono, also declared February 28 “Alice Ball Day.” In 2007, the University of Hawaii posthumously awarded her with the Regents’ Medal of Distinction.

Paul Wermarger is a scholar who researched Ball for years and established a scholarship on her behalf. “Not only did she overcome the racial and gender barriers of her time to become one of the very few African American women to earn a master’s degree in chemistry, [but she] also developed the first useful treatment for Hansen’s disease. Her amazing life was cut too short at the age of 24. Who knows what other marvelous work she could have accomplished had she lived.”

Recommended reading

Alice Augusta Ball: The African-American chemist who pioneered the first viable treatment for Hansen’s Disease. (Clinics in Dermatology, 2023)

Women who had their work stolen from them by men (History Collection, 2021)

A woman who changed the world (University of Hawaii Foundation, 2024)