(Photo credit: Library of Congress)

In honour of Black History Month, we are pleased to feature a series of stories celebrating the contributions Black individuals have made to our understanding of infectious diseases and how to prevent and treat them. Each story is written by a member of EPIC’s Trainee Advisory Committee.

February 2, 2024

By Manisha Kabi

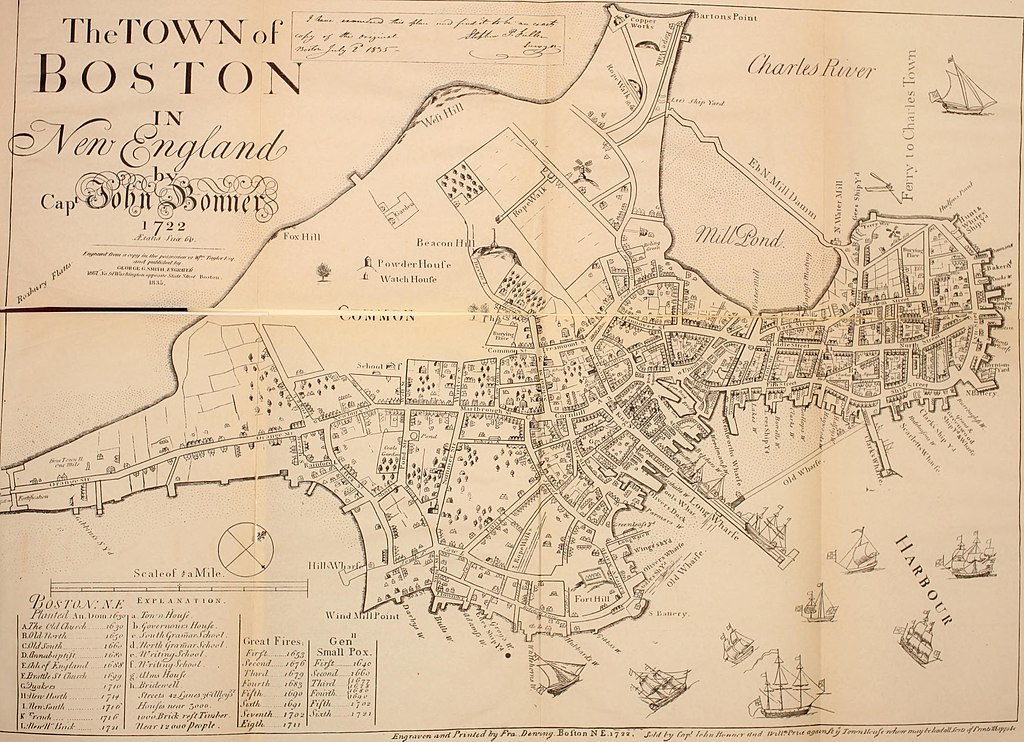

In the early 1700s, nearly a century prior to Edward Jenner’s groundbreaking development of an effective smallpox vaccine, the disease had already reached New England and other American colonies. The 1721 smallpox epidemic ravaged the city of Boston, infecting over half of its population and resulting in the deaths of 850 people, equivalent to more than 14 percent of the total population.

The outbreak also introduced the concept of inoculation to America, which was later credited with saving numerous lives. Inoculation, a process of inducing immunity by deliberately introducing infectious agents into the body, was a precursor to vaccines crucial in today’s battle against COVID-19 and other infectious diseases.

In the history of inoculation, the contributions of the slave Onesimus are often neglected.

Onesimus was an African man sold into slavery to the Boston Puritan minister Cotton Mather. According to Mather’s records, Onesimus was from “Guaramantee,” which was likely an anglicized reference to Kormontse, a town in present-day Ghana. While there are no records that indicate his birth name, we do know that Onesimus was not the name he was born with.

In a 1716 letter to the Royal Society of London, Mather wrote that when asked if he had contracted smallpox, Onesimus responded with a cryptic “yes and no.” He further went on to disclose that after experiencing smallpox, he had undergone an operation that provided him with a form of immunity. He asserted that those who dared to undergo this process would be permanently free from the fear of contagion.

The procedure Onesimus described was variolation, a now outdated technique that has been replaced by vaccination. A type of inoculation, variolation involved rubbing pus from a person with smallpox into an open wound on the arm of an uninfected individual. Conducted in a controlled manner under the supervision of a physician, this method aimed to induce milder symptoms while conferring immunity. Mather was captivated by the idea of deliberately exposing people to smallpox to immunize them against a potentially severe natural infection. He hoped that this technique could help prevent smallpox and limit the devastation caused by the outbreak.

Upon researching, Mather found that, in addition to Africa, the practice of variolation had been used for hundreds of years in Turkey, China and India. He recorded in his diary, “the new Method used by the Africans and Asiaticks, to prevent and abate the Dangers of the Small-Pox, and infallibly to save the Lives of those that have it wisely managed upon them.”

Mather’s efforts to help prevent smallpox using this approach faced racially and religiously motivated opposition. Many critics dismissed the idea simply because it was practiced by cultures in Africa and Asia. Preachers argued that exposing humans to harmful diseases went against God’s will.

In 1721, Mather and Zabdiel Boylston, the lone physician in Boston who supported the idea of variolation, decided to use the outbreak as an opportunity to test the efficacy of the new procedure. Boylston inoculated his own son, two enslaved people working in his household and between 180 and 250 residents of Boston. Of the inoculated individuals, only six succumbed to smallpox, resulting in a mortality rate of one in 40 compared to the one in seven deaths seen among the general Boston population who did not undergo the procedure. These results showed that those who were exposed to smallpox first through variolation were almost six times less likely to die than those who got it naturally.

This early test of variolation played a crucial role in paving the way for vaccination.

Whether Onesimus was able to witness the success of the technique he introduced remains unclear. Almost all existing information about Onesimus comes from Mather’s diary, supplemented by occasional references in later church and civic records. We do know that Onesimus was married and that the couple had at least one son, who died in 1714. Onesimus managed to buy partial freedom but continued to serve Mather. While little is known about his subsequent whereabouts and the details of his later life, his contributions to smallpox vaccination left a lasting legacy on the field.

In 1980, smallpox, one of the deadliest and most feared diseases, was declared completely eradicated thanks to worldwide vaccination efforts. It remains the only infectious disease ever to be wiped out.

Recommended reading

How an Enslaved Man Helped Boston Battle a Devastating Disease 300 Years Ago (NBC10 Boston, 2021)

Meet Onesimus, The Enslaved Man Who Saved Colonial Boston From Smallpox (Forbes, 2021)

How an Enslaved African Man in Boston Helped Save Generations from Smallpox (History, 2019)

Onesimus and the 1721 Smallpox Outbreak in Boston (Smithsonian Learning Lab)