August 14, 2023

By Ishani Nath

It seems appropriate that the Toronto offices for Kamran Khan’s BlueDot, which uses artificial intelligence to flag potential infectious disease outbreaks around the world, are located at the edge of Lake Ontario. Similar to a lighthouse, BlueDot signals when there’s danger ahead.

“We use the internet as a medium for surveillance to detect early signals of outbreaks anywhere in the world before they’re officially reported by public health agencies,” explains Khan, a professor of medicine in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine and the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto and a member of the Centre for Vaccine Preventable Diseases (CVPD). He breaks BlueDot’s work down into three key components: identifying threats early, rapidly assessing their risks and likely trajectories, and helping organizations to turn these insights into swift action.

“The whole purpose here is to compress time, because ultimately, time is the enemy when you’re dealing with an outbreak,” he says.

BlueDot’s intelligence platform combines a computer’s ability to understand human language, known as natural language understanding (NLU), and machine learning, a form of AI that imitates humans’ ability to learn and gradually become more accurate. The platform sorts through massive volumes of online information— ranging from news reports, social media sites, government websites, and more — from around the globe, in over 130 languages, every 15 minutes of every day.

“We’ve basically trained a machine to pick up early clues around the world and around the clock,” explains Khan, who is also a member of the Emerging and Pandemic Infections Consortium. These clues get cross-referenced with historic data to determine what is outside of the norm, and then triaged into high, medium, and low risk threats. Global data — including commercial air travel data, climate conditions, mosquito observances, and population demographics — are also added to the mix to determine whether a threat could spread.

This data analytic sequence is how BlueDot accurately predicted a Zika virus outbreak in Florida six months before it occurred, and sounded the alarm about COVID-19 nearly a week before it was officially reported by public health organizations like the CDC and WHO.

As COVID-19 restrictions have eased around the world, public health experts are now shifting focus to the next set of emerging global threats — what could spark the next pandemic, and will we be ready? CVPD’s Ishani Nath sat down with Khan to learn how BlueDot uses artificial and human intelligence to help answer these questions and more.

I think there’s a fear when it comes to AI that we’ll become too dependent on machines. What role do humans play in BlueDot’s data?

Our belief is that machines should play to its strengths, and humans should play to theirs. There’s a whole process of using machine learning for gathering, organizing and ingesting unstructured data that’s multilingual and creating structure out of it 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. And then there’s a series of analytics and human intelligence that helps us differentiate what threats demand our immediate attention and anticipate where, when, and how they will impact the health of populations around the globe. Recent advances in generative AI are also creating opportunities for machines to produce “intelligence briefs” — but given the vital importance of these outputs, there will always be a need for human oversight.

For example, we first have to determine whether a threat appearing somewhere in the world is unusual. It’s important to remember that machine learning is only as good as the historic data that we train it on. But when we’re dealing with newly emerging diseases, we are often dealing with threats where there is little or no historic data. For instance, if we identify an outbreak of an influenza-like-illness occurring in the northern hemisphere in July, we know that is unusual compared with observed historic trends. But for some newly emerging threats like COVID-19 where we don’t have historic data, we have to tap into our in-house expertise in public health sciences, clinical medicine, pediatric infectious disease, and veterinary sciences, while also collaborating with experts from academia and governments around the world to rapidly characterize and assess those novel threats.

How can this information improve how threats get addressed, such as with vaccines?

Well, we’re not just considering what constitutes a vaccine preventable disease today. By working with private sector organizations like pharmaceutical companies, we’re helping support decisions about what they should be investing in in terms of R&D to develop new vaccines for diseases where the landscape is going to significantly change in the future, for example, because of climate change.

And when vaccines are in market, are they manufacturing enough in relation to forthcoming demand? Are they producing it at the right time? Are they distributing it optimally and equitably? BlueDot’s public and private sector clients are using our intelligence to support key decisions not just about what’s happening now, but also what’s coming next.

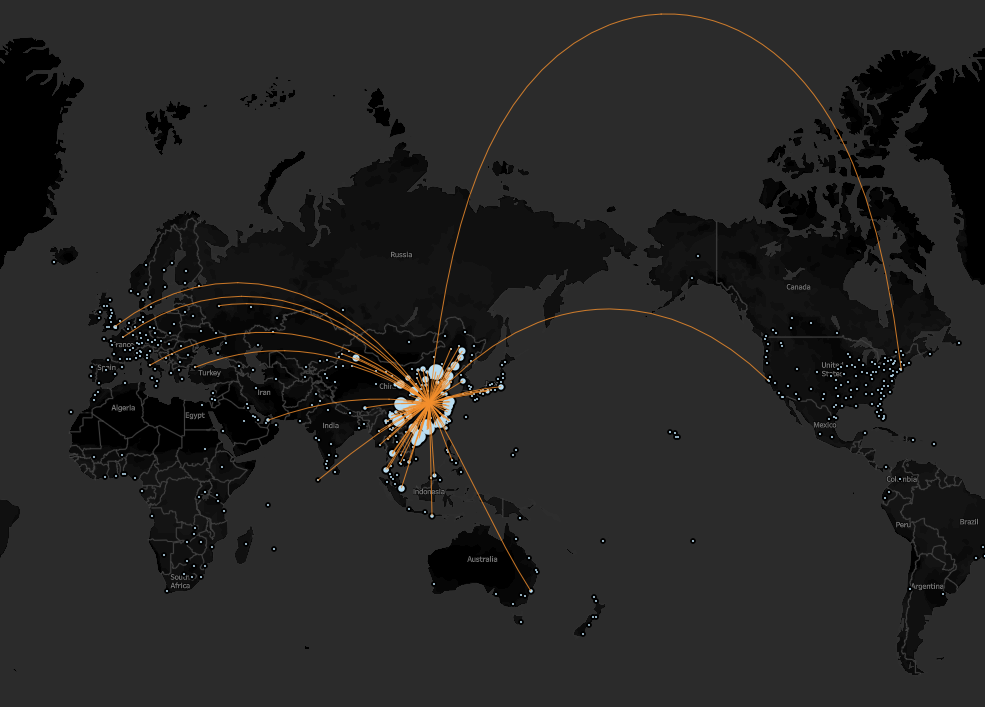

Data showing travellers from Wuhan, 2019 (BlueDot)

You mentioned climate change. Since 2020, BlueDot has added many new data sources to its platform. Do you also consider climate and environmental data?

Yes. Going back to Zika for example, what we were able to determine, and publish in The Lancet, is where we would expect lots of infected travellers and no local outbreak versus lots of infected travellers, and environmental conditions suitable for a local outbreak. What happened six months later is entirely aligned with what we anticipated.

We’re now working on taking the latest climate change models and intersecting them with ecological models for mosquitoes and insects so we can anticipate where those insects will survive and thrive in new areas. If you don’t have the mosquito that can transmit a particular virus, then there’s no possibility of a local outbreak from that virus. But these ranges are changing. In some cases, it’s actually becoming too hot and they’re not able to effectively transmit. But in other cases, conditions are becoming more hospitable.

Things are changing pretty quick. How far into the future do these data look?

We’re doing these forecasts looking 10 years into the future. The main reason we’re looking out that far, realizing there’s more uncertainty as you go further out, is that we are working with pharmaceutical and life sciences companies that develop and manufacture vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, PPE, disinfectants, and more. Their interests are understanding and anticipating future demand. Do they invest in a chikungunya vaccine or a vaccine for a different infectious disease? A vaccine manufacturer has to consider: What am I investing in today, how many lives could it protect, and is this a sound business decision recognizing that might take a decade or more to actually bring that vaccine to market?

What’s next for BlueDot?

Building on top of large language models (LLMs) like GPT, we’ve developed some early capabilities where you can ask our platform questions in natural language. Like, “every day, tell me how many cases of COVID there are in my location this week and if there’s an increase of 10% or more above baseline, notify me.” Or, “tell me how many travelers on flights are coming from London to Toronto in the next three months and the likelihood of an imported case of measles showing up.” We’re still actively in R&D mode but building on top of LLMs is showing a lot of promise.

We talked about using this technology to predict outbreaks 10 years from now. How does working in this space shape how you personally feel about the future?

I’m excited by the fact that technology can help humans in powerful ways, but understand that humans have to help themselves. I often quote the Spanish philosopher George Santayana who said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” My worry is we’re quick to forget and that we will repeat the cycle of panic followed by neglect until humanity realizes we have to be proactive — because we know it’s a certainty we will be dealing with more threats in the future. What I often ask myself is, what things can I do today that will have a tangible and positive impact on the lives of others?