Originally published on Dalla Lana School of Public Health

By Françoise Makanda, Communications Officer at DLSPH

In less than three months, a small lab at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health is helping healthcare providers validate their mask reprocessing processes by testing the efficiency of filters at capturing fine particles.

The lab in the Gage building is also supporting a literature review for back-to-work guidelines.

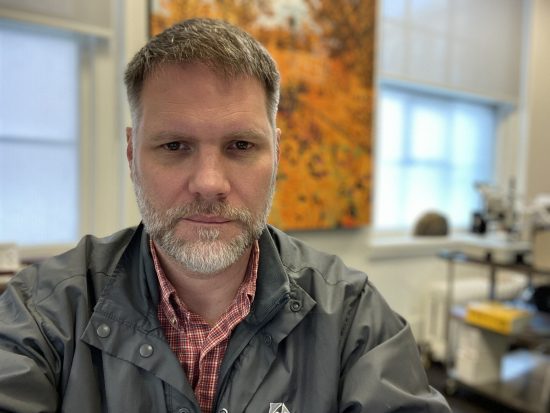

“No one in Canada had really bothered to establish a Canadian mask testing facility before the pandemic. The few labs in Canada that have offered tests do it by subcontracting either the labs in the United States or labs in Europe or Asia to do the testing,” says James Scott, Project Lead and Professor at DLSPH in the Occupational & Environmental Health Division.

“Under ordinary circumstances that subcontracting hasn’t mattered much but under the current circumstances we need some domestic capacity to be able to do this testing.”

Scott has prepared himself for such eventualities. The Occupational and Environmental Health team has long been involved in aerosol testing and maintains a collection of high-end research equipment, but the lab was not intended to serve as a mask testing facility.

“Mask testing is the thing that takes the longest,” says Scott. “We have equipment suitable for that kind of testing but the workflow is cumbersome and not purposely designed for it so it takes a lot longer to do than if we were properly set up. But, the results are just as good.”

Luckily, with grants and support, Scott and his team will have more equipment to provide this vital work. Scott’s project is one of the 30 research projects to receiving funding through the University of Toronto’s $9-million Toronto COVID-19 Action Fund and additional generous funds from the Temerty Foundation.

Although Scott’s team has been looking at all kinds of masks, including do-it-yourself projects from the community, the lab is heavily focused on testing hospital decontamination processes for N95 masks. Health Canada requires hospitals to prove their disinfection protocols work to clean N95 masks to be reused, typically by the same person.

In his lab, Scott tests masks with a chamber that contains a mannequin that replicates the human face. It has a trachea that draws air through the mask. The goal is to ensure the masks draw on these particles without getting into the mannequins’ trachea. Airborne particles in the chamber model how a virus would deposit on a mask under normal breathing conditions.

“They also want to make sure that the disinfection protocol appropriately kills the stuff that might be on the masks,” says Scott. “The second piece of what we’re doing is loading the masks with test virus particles called bacteriophages, which are structurally similar to SARS coronavirus, to make sure the process actually kills the adherent virus particles.”

Researchers then measure how many particles are in front and behind the masks. The masks must be capable of capturing infectious particles with a greater than 95 per cent efficiency to pass the test.

Scott’s team was involved in validating the full-face snorkel mask developed at Sunnybrook hospital, an alternative to the N95. As a high-grade respirator, Scott says that the mask has the potential to offer really good protection in a way that doesn’t obstruct healthcare workers’ faces. They are working on the snorkel mask’s next iteration.

“We have had to develop some separate technology to be able to validate the mask,” says Scott. “We 3D printed actual face scans and attached those to the mannequin head. We’ve got one with artificial skin that creates a more proper and realistic seal with a snorkel mask.”

Scott can’t keep count on the number of processes his team has had to review. The work has increased by a tenfold outside of mask validation– the lab has welcomed six students in early May to help out. The orientation was quick and the task was simple: A scoping review to help the Canadian Standard Association to develop “back to work” guidelines.

Occupational and Environmental Health student Serena Mo is treating this new experience as an asset for her future as an occupational hygienist.

“It’s interesting how quickly other organizations have come up with recommendations and how to go about this pandemic that we’re facing,” says Mo. “There is research that’s continuously coming out. And even though it’s a very sad situation, there’s a lot of room for innovation and ideas on how to go about this pandemic.”

For now, Scott will continue to build PPE testing capacity in his lab for the next cohort of students. “I’ll probably be on to the next thing, but I want to make sure that we build the capacity here to do this and to keep it going – both the human resources and the technical resources to be able to do it properly.”